In 1996, when I launched my tiger study in the Panna Tiger Reserve, I was a faculty member of the Wildlife Institute of India. My retired Forest Officer father visited me often in Dehra Dun and listening to his stories, one lesson that stayed with me was that no two tigers are the same - ‘never trust a tiger you don’t know’ was his excellent advice.

After ten years of working with individually known tigers, I can see how truly he spoke. Individual tigers are as different as you and I. I learnt that, like humans, they could also have preferences, likes and dislikes and different ways of doing things. In the book “The Rise and Fall of the Emerald Tigers”, I describe the differences we observed in the study tigers of Panna.

Baavan, the matriarch of the Panna Reserve was very temperamental. We learned very quickly that she did not like us to be too close; we soon grew to understand the distance she was comfortable with. As long as we maintained this distance, we could stay and monitor her for hours without it bothering her. She never liked open spaces and preferred to remain under some cover. She would also never slip away quietly as many tigers will do when faced with human presence. She was different; she might surprise us by a mock charge, turn back and then walk away. This temperament made it more of a struggle to catch and radio collar her, although we did manage to change her collar several times. But this was only because we learned to respect her tolerance limits and with patience, wait to find the right opportunity. It could take us weeks to find her in a suitable place and relaxed enough to allow our approach for darting.

The matriarch, Baavan

The matriarch, Baavan

Observing individual tigers with different personalities helped us understand how differently tigers behave in relation to their environment. In September and October, Baavan was rarely seen with large prey kills and we wondered what was she feeding on during these months. Continuous monitoring on elephant back revealed that she was mainly catching newly born sambar fawns. None of the other tigers showed this behaviour as consistently. Baavan would walk a zigzag course, flushing fawns and picking them up with ease. Her daughter, Sayani, on the other hand, favoured nilgai and had a distinctive approach to catching them in tall grass areas. Before the fire line is burnt on either side of the road, we noticed that most of her nilgai kills were along the roadside that goes through the tall grass habitats. The park’s management cut a line of grass 2-3 feet wide and twenty feet back on either side of the road. This is to control the fire’s spread when they burn the road edges as fire breaks. Sayani found that this break in cover provided a very appropriate space that allowed her a stealthy but fast approach to the prey. We noticed that her nilgai kills were mainly close to natural breaks like small rivulets within a tall grass habitat. The combination of tall grass with a break in its cover consistently provided Sayani with a tactic that she used only for nilgai and no other prey.

I narrate here another example of how strong individual preference can be for some tigers; it is a fun story. Baavan visited an area called Jamunihai seha, a deep gorge surrounded by 120-150 feet high escarpments very regularly. The only way was to go on foot. One day as soon as our tracking team got out of the jeep, to my amusement, I noticed they were busy arguing and betting on something. I asked what was going on. I was told that they were betting on Baavan’s location, whether she would be on the left or right side of the Ficus tree. They were confident about the rock but they had observed that before noon she usually lay on the rock to the right of the tree and then moved to the left of the tree after two pm. The team were all smiles when we located her on the expected side of the tree. Of course, we were not right every time but the point of this story is that it shows her preference for a particular micro-habitat and how very selective she was about it. Similar tendencies could be noticed in other tigers’ movement patterns too; they were often very predictable. If we had located Madla, one of the males we were monitoring, in Panna seha which was about 6-8 km from our camp, we knew there was an excellent chance that a couple of days later he would pass our field camp. Alarm calls would forewarn us and we would sit in anticipation of watching him walking past our camp; we were rarely disappointed.

Shyness, boldness and aggression can be visible at a very young age and many cubs grow to adulthood with these traits. For young males dispersing into the unknown, some of these traits can be very handy and will allow the dispersers to survive better in a human-dominated environment. A kind of selection takes place in these situations, where males equipped with particular tendencies that are appropriately suited to successfully avoiding human-caused mortality, survive better and maximize their reproductive potential. Others, whose traits are less suited for these conditions, may perish. The two males we knew had survived such selection and were experts, though their strategies to avoid humans were quite different. What was common to both males was that neither were aggressive towards humans. Despite them being some of the biggest tigers we have ever known, I do not remember seeing any aggression from either of these two hulks. Discretion was the better part of valour for both of them. In areas with human movement, one of the two males would feed only once on his kill, then leave and not return, however much meat was still on it. The other would remain with his kill to finish eating but stay quiet and hidden even when humans were close by. However, occasionally if eye contact was made, it might spook him enough to slink away. Both were successful males, despite their individuality.

Male-91 on the left had free run until Madla (on the right) arrived on the scene.

Male-91 on the left had free run until Madla (on the right) arrived on the scene.

The three siblings, daughters from the first litter of Baavan, were all different too. One of the siblings, we called her F-111, was shy and reclusive so we hardly saw her. She would very successfully melt away quietly before we could spot her and as a result, we have very few photos of this tigress. We never saw any aggression from her, but she was a nervous type: she changed litter locations unusually frequently and always approached her litter very secretively. Her territory included two villages and more human movement than the other tigers’, so it may have been her wariness that allowed her to survive as long as she did. Sayani and Judi, the other two siblings, were more tolerant of human presence. How these individual personalities help tigers to maximise their reproductive success can be a fascinating subject for a study.

F111 and Judi, two of Baavan’s daughters. The third sister Sayani, is the gentle tigress in the first, opening, image.

F111 and Judi, two of Baavan’s daughters. The third sister Sayani, is the gentle tigress in the first, opening, image.

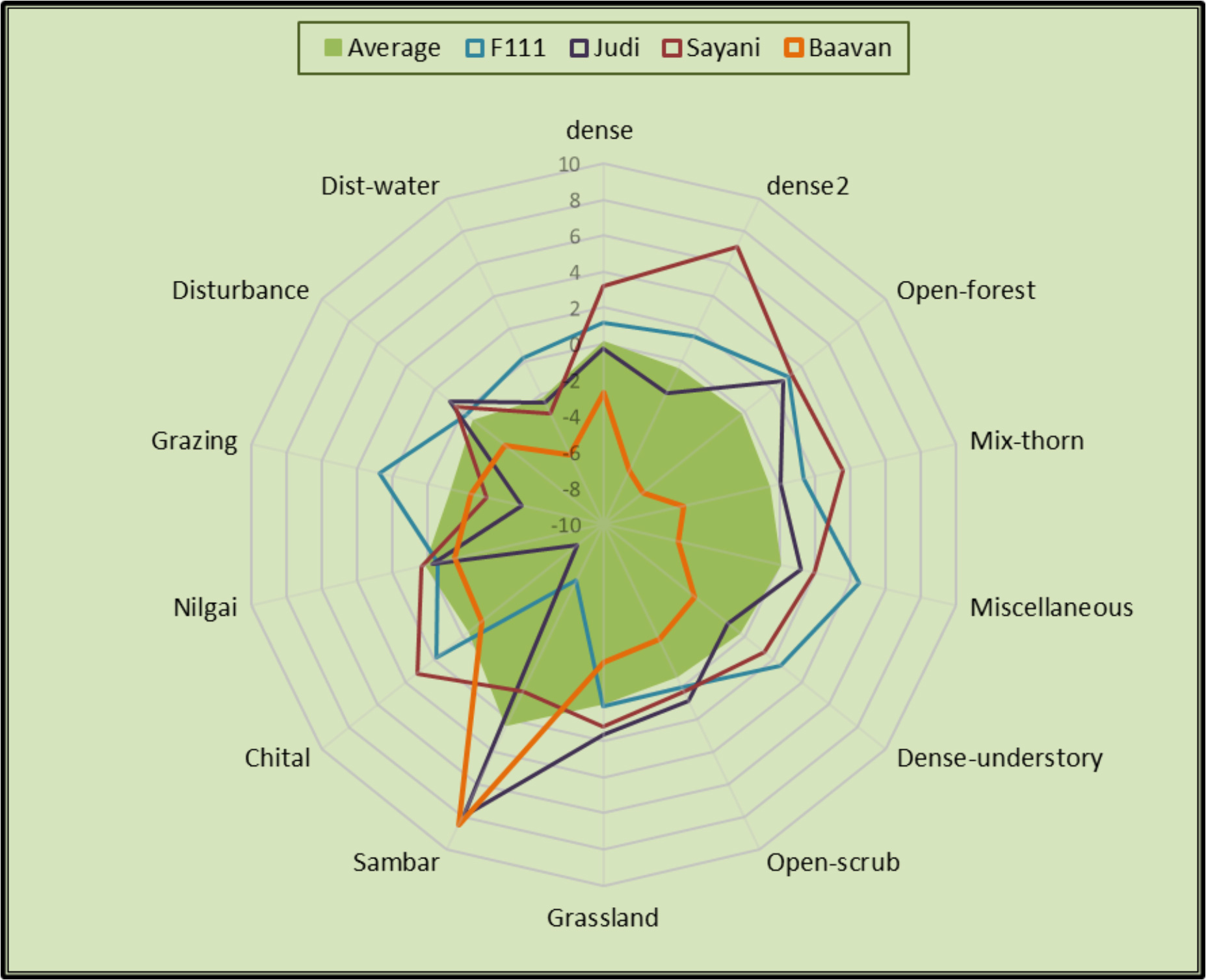

When we write on the ecology or behaviour of tiger or any other animal, many of us scientists tend to overlook individual variations in space use, prey preferences and movement patterns. Our studies usually describe individual variations as the unpredictable (stochastic) noise around a mean. In these calculations, we assume that all individuals behave the same way. In fact populations include a range of individuality that is responding to prevailing conditions in different ways to achieve maximum reproductive success (Darwinian ‘fitness’). This individual behaviour can be associated with cost and benefits. When the outcome of an individual behaviour results in net benefits, it can increase fitness for that individual. When net outcome for the population is expressed as an average it does not accurately reflect the variable costs and benefits associated with individuals.

This diagram illustrates how individual preferences are disguised when the resource selections of four different tigresses are combined to form an average

This diagram illustrates how individual preferences are disguised when the resource selections of four different tigresses are combined to form an average

Science does recognise the importance of individual behaviour that is consistent over time; this could be individual personality, agonistic behaviour or aggressiveness, variability in individual responses to environment, tendencies and shyness-boldness. These inter-individual behaviours are described in science as “behavioural syndromes” and have been documented in many animal groups. An increasing number of studies now document the importance of individual-level variations, because it influences population-level processes such as space use, habitat selection, dispersal etc. and most importantly they are linked to the fitness of a population. This needs to be taken into account when planning conservation for our tiger; there is no universal single preferred habitat or prey, and therefore no single solution for the tiger.